what event ended the transportation of felons to north america

Women in England mourning their lovers who are soon to be transported to Botany Bay, 1792

Penal transportation or transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; subsequently, specifically established penal colonies became their destination. While the prisoners may have been released once the sentences were served, they generally did non accept the resources to return home.

Origin and implementation [edit]

Adjournment or forced exile from a polity or society has been used as a penalisation since at to the lowest degree the 5th century BC in Ancient Greece. The practice of penal transportation reached its height in the British Empire during the 18th and 19th centuries.[one]

Transportation removed the offender from society, mostly permanently, but was seen as more than merciful than capital punishment. This method was used for criminals, debtors, armed forces prisoners, and political prisoners.[ citation needed ]

Penal transportation was also used as a method of colonization. For case, from the primeval days of English language colonial schemes, new settlements beyond the seas were seen every bit a way to convalesce domestic social problems of criminals and the poor likewise as to increase the colonial labour forcefulness,[1] for the overall benefit of the realm.[2]

United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and the British Empire [edit]

Initially based on the royal prerogative of mercy,[3] and later on under English police, transportation was an alternative judgement imposed for a felony. Information technology was typically imposed for offences for which decease was deemed as well severe. Past 1670, as new felonies were defined, the option of beingness sentenced to transportation was allowed.[4] [5] Forgery of a document, for example, was a capital law-breaking until the 1820s, when the penalty was reduced to transportation. Depending on the crime, the judgement was imposed for life or for a set period of years. If imposed for a period of years, the offender was permitted to return home later serving his fourth dimension, but had to make his own manner dorsum. Many offenders thus stayed in the colony as free persons, and might obtain employment as jailers or other servants of the penal colony.

England transported its convicts and political prisoners, too equally prisoners of war from Scotland and Ireland, to its overseas colonies in the Americas from the 1610s until early on in the American Revolution in 1776, when transportation to America was temporarily suspended by the Criminal Police force Act 1776 (16 Geo. 3 c. 43).[half dozen] The practice was mandated in Scotland by an human action of 1785, but was less used at that place than in England. Transportation on a large scale resumed with the difference of the Start Fleet to Australia in 1787, and connected in that location until 1868.

Transportation was not used by Scotland earlier the Act of Union 1707; following spousal relationship, the Transportation Human activity 1717 specifically excluded its use in Scotland.[seven] Under the Transportation, etc. Act 1785 (25 Geo. 3 c. 46) the Parliament of U.k. specifically extended the usage of transportation to Scotland.[8] It remained piddling used[nine] nether Scots Police force until the early 19th century.

In Australia, a captive who had served function of his time might utilize for a ticket of get out, permitting some prescribed freedoms. This enabled some convicts to resume a more normal life, to marry and raise a family unit, and to contribute to the development of the colony.

Historical background [edit]

The tendency towards more flexibility of sentencing [edit]

In England in the 17th and 18th centuries criminal justice was severe, later on termed the Encarmine Lawmaking. This was due to both the peculiarly large number of offences which were punishable by execution (usually by hanging), and to the limited choice of sentences available to judges for convicted criminals. With modifications to the traditional benefit of clergy, which originally exempted merely clergymen from the full general criminal law, it developed into a legal fiction by which many common offenders of "clergyable" offences were extended the privilege to avert execution.[ten] Many offenders were pardoned as it was considered unreasonable to execute them for relatively minor offences, simply under the rule of law, it was equally unreasonable for them to escape penalization entirely. With the development of colonies, transportation was introduced as an alternative punishment, although legally information technology was considered a condition of a pardon, rather than a judgement in itself.[11] Convicts who represented a menace to the customs were sent away to distant lands. A secondary aim was to discourage criminal offence for fear of being transported. Transportation continued to be described every bit a public exhibition of the king'southward mercy. It was a solution to a real problem in the domestic penal arrangement.[12] At that place was also the hope that transported convicts could be rehabilitated and reformed past starting a new life in the colonies. In 1615, in the reign of James I, a commission of the quango had already obtained the power to choose from the prisoners those that deserved pardon and, consequently, transportation to the colonies. Convicts were chosen advisedly: the Acts of the Privy Council showed that prisoners "for strength of bodie or other abilities shall be thought fit to be employed in foreign discoveries or other services beyond the Seas".[13]

During the Commonwealth, Oliver Cromwell overcame the popular prejudice confronting subjecting Christians to slavery or selling them into strange parts, and initiated group transportation of military[fourteen] and civilian prisoners.[fifteen] With the Restoration, the penal transportation organization and the number of people subjected to information technology, started to change inexorably betwixt 1660 and 1720, with transportation replacing the simple belch of clergyable felons subsequently branding the thumb. Alternatively, under the second act dealing with Moss-trooper brigands on the Scottish border, offenders had their benefit of clergy taken away, or otherwise at the judge's discretion, were to be transported to America, "at that place to remaine and not to returne".[sixteen] [17] There were diverse influential agents of change: judges' discretionary powers influenced the law significantly, but the king'south and Privy Council's opinions were decisive in granting a royal pardon from execution.[eighteen]

The system changed 1 step at a time: in February 1663, later on that get-go experiment, a bill was proposed to the House of Commons to allow the transporting of felons, and was followed by another bill presented to the Lords to allow the transportation of criminals convicted of felony within clergy or petty larceny. These bills failed, but it was clear that modify was needed.[19] Transportation was non a sentence in itself, but could exist bundled by indirect means. The reading test, crucial for the benefit of clergy, was a fundamental characteristic of the penal organisation, merely to prevent its abuse, this pardoning process was used more strictly. Prisoners were carefully selected for transportation based on information nigh their character and previous criminal record. It was arranged that they neglect the reading test, merely they were then reprieved and held in jail, without bail, to allow time for a imperial pardon (bailiwick to transportation) to exist organised.[20]

Transportation equally a commercial transaction [edit]

Joseph Lycett, an creative person transported for forging banking company notes, The residence of Edward Riley Esquire, Wooloomooloo, Near Sydney N. S. W., 1825, hand-coloured aquatint and etching printed in nighttime bluish ink. Australian print in the tradition of British decorative product.

Transportation became a business: merchants chose from among the prisoners on the basis of the need for labour and their probable profits. They obtained a contract from the sheriffs, and after the voyage to the colonies they sold the convicts as indentured servants. The payment they received also covered the jail fees, the fees for granting the pardon, the clerk's fees, and everything necessary to authorise the transportation.[21] These arrangements for transportation continued until the stop of the 17th century and across, but they diminished in 1670 due to certain complications. The colonial opposition was one of the chief obstacles: colonies were unwilling to collaborate in accepting prisoners: the convicts represented a danger to the colony and were unwelcome. Maryland and Virginia enacted laws to prohibit transportation in 1670, and the king was persuaded to respect these.[21]

The penal system was also influenced by economics: the profits obtained from convicts' labour additional the economy of the colonies and, consequently, of England. Nonetheless, information technology could be argued that transportation was economically deleterious because the aim was to enlarge population, not diminish it;[22] but the character of an individual captive was likely to harm the economic system. King William'south War (1688–1697) (part of the Nine Years' War) and the State of war of the Castilian Succession (1701–14) adversely affected merchant aircraft and hence transportation. In the post-war period at that place was more law-breaking[23] and hence potentially more executions, and something needed to be done. In the reigns of Queen Anne (1702–14) and George I (1714–27), transportation was not easily arranged, but imprisonment was not considered plenty to punish hardened criminals or those who had committed capital offences, so transportation was the preferred punishment.[24]

Transportation Act 1717 [edit]

There were several obstacles to the utilise of transportation. In 1706 the reading test for claiming benefit of clergy was abolished (five Anne c. 6). This allowed judges to sentence "clergyable" offenders to a workhouse or a house of correction.[24] Only the punishments that so applied were not enough of a disincentive to commit criminal offense: some other solution was needed. The Transportation Act was introduced into the Firm of Commons in 1717 under the Whig authorities. It legitimised transportation every bit a straight judgement, thus simplifying the penal process.[25]

Non-capital letter convicts (clergyable felons ordinarily destined for branding on the pollex, and petty larceny convicts usually destined for public whipping)[26] were directly sentenced to transportation to the American colonies for seven years. A sentence of xiv years was imposed on prisoners guilty of capital offences pardoned by the king. Returning from the colonies before the stated flow was a capital offence.[25] The bill was introduced by William Thomson, the Solicitor General, who was "the architect of the transportation policy".[27] Thomson, a supporter of the Whigs, was Recorder of London and became a judge in 1729. He was a prominent sentencing officer at the Erstwhile Bailey and the homo who gave important data about capital offenders to the cabinet.[28]

One reason for the success of this Act was that transportation was financially plush. The system of sponsorship by merchants had to exist improved. Initially the government rejected Thomson's proposal to pay merchants to transport convicts, but 3 months after the showtime transportation sentences were pronounced at the Old Bailey, his suggestion was proposed once again, and the Treasury contracted Jonathan Forward, a London merchant, for the transportation to the colonies.[29] The business was entrusted to Forward in 1718: he was paid £iii (£5 in 1727) for each prisoner transported overseas. The Treasury also paid for the transportation of prisoners from the Home Counties.[30]

The "Felons' Act" (equally the Transportation Act was called) was printed and distributed in 1718, and in April xx-vii men and women were sentenced to transportation.[31] The Act led to significant changes: both petty and grand larceny were punished by transportation (seven years), and the sentence for whatsoever non-uppercase offence was at the gauge's discretion.[32] In 1723 an Deed was presented in Virginia to discourage transportation by establishing complex rules for the reception of prisoners, but the reluctance of colonies did not cease transportation.[33]

In a few cases before 1734, the court inverse sentences of transportation to sentences of branding on the thumb or whipping, by convicting the accused for lesser crimes than those of which they were accused.[34] [35] This manipulation stage came to an terminate in 1734. With the exception of those years, the Transportation Act led to a decrease in whipping of convicts, thus fugitive potentially inflammatory public displays. Clergyable discharge connected to be used when the accused could not be transported for reasons of historic period or infirmity.[36]

Women and children [edit]

Penal transportation was not limited to men or even to adults. Men, women, and children were sentenced to transportation, simply its implementation varied by sex and historic period. From 1660 to 1670, highway robbery, burglary, and horse theft were the offences near often punishable with transportation for men. In those years, five of the nine women who were transported after being sentenced to death were guilty of simple larceny, an offence for which benefit of clergy was not bachelor for women until 1692.[37] Also, merchants preferred immature and athletic men for whom there was a demand in the colonies.

All these factors meant that nigh women and children were but left in jail.[21] Some magistrates supported a proposal to release women who could non be transported, but this solution was considered absurd: this caused the Lords Justices to order that no distinction exist made between men and women.[38] Women were sent to the Leeward Islands, the only colony that accustomed them, and the government had to pay to send them overseas.[39] In 1696 Jamaica refused to welcome a grouping of prisoners because nearly of them were women; Barbados similarly accepted convicts but not "women, children nor other infirm persons".[forty]

Thanks to transportation, the number of men whipped and released macerated, but whipping and discharge were chosen more than often for women. The reverse was true when women were sentenced for a capital offence, simply actually served a lesser sentence due to a manipulation of the penal organisation: i advantage of this sentence was that they could be discharged thanks to do good of clergy while men were whipped.[41] Women with immature children were besides supported since transportation unavoidably separated them.[41] The facts and numbers revealed how transportation was less frequently applied to women and children because they were unremarkably guilty of modest crimes and they were considered a minimal threat to the community.[34]

The end of transportation [edit]

The outbreak of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) halted transportation to America. Parliament claimed that "the transportation of convicts to his Majesty's colonies and plantations in America ... is found to exist attended with diverse inconveniences, specially by depriving this kingdom of many subjects whose labour might be useful to the community, and who, by proper care and correction, might be reclaimed from their evil course"; they and so passed "An human action to qualify ... the punishment by difficult labour of offenders who, for certain crimes, are or shall go liable to be transported to whatsoever of his Majesty's colonies and plantations."[42] For the ensuing decade, men were instead sentenced to difficult labour and women were imprisoned. Finding alternative locations to send convicts was not easy, and the act was extended twice by the Criminal Police force Act 1778 (eighteen Geo. 3 c. 62) and the Criminal Law Deed 1779 (19 Geo. 3, c. 54).[43] This resulted in a 1779 inquiry by a Parliamentary Commission on the entire subject area of transportation and punishment; initially the Penitentiary Deed was passed, introducing a policy of state prisons as a measure to reform the system of overcrowded prison hulks that had developed, but no prisons were always built as a result of the human action.[44] The Transportation, etc. Deed 1784 (24 Geo. 3 c. 56)[45] and the Transportation, etc. Human activity 1785 (25 Geo. 3 c. 46)[eight] also resulted to help alleviate overcrowding. Both acts empowered the Crown to engage certain places inside his dominions, or exterior them, every bit the destination for transported criminals; the acts would motion convicts around the country as needed for labour, or where they could be utilized and accommodated.

The overcrowding situation and the resumption of transportation would be initially resolved past Orders in Council on 6 December 1786, by the decision to establish a penal colony in New South Wales, on land previously claimed for United kingdom in 1770,[46] [47] [48] but as yet not settled by Britain or any other European power. The British policy toward Australia, specifically for use as a penal colony, within their overall plans to populate and colonise the continent, would differentiate it from America, where the use of convicts was only a small adjunct to its overall policy.[49] In 1787, when transportation resumed to the called Australian colonies, the far greater distance added to the terrible experience of exile, and it was considered more severe than the methods of imprisonment employed for the previous decade.[50] The Transportation Act 1790 (30 Geo. 3 c. 47) officially enacted the previous orders in quango into police force, stating "his Majesty hath declared and appointed... that the eastern coast of New South Wales, and the islands thereunto next, should be the identify or places beyond the seas to which certain felons, and other offenders, should be conveyed and transported ... or other places". The act also gave "say-so to remit or shorten the time or term" of the sentence "in cases where it shall announced that such felons, or other offenders, are proper objects of the royal mercy"[51]

At the kickoff of the 19th century, transportation for life became the maximum penalty for several offences which had previously been punishable by death.[50] With complaints starting in the 1830s, sentences of transportation became less common in 1840 since the organisation was perceived to be a failure: crime connected at high levels, people were non dissuaded from committing felonies, and the atmospheric condition of convicts in the colonies were inhumane. Although a concerted program of prison house building ensued, the Curt Titles Act 1896 lists seven other laws relating to penal transportation in the first half of the 19th century.[52]

The system of criminal penalization by transportation, as it had adult over nearly 150 years, was officially concluded in Britain in the 1850s, when that judgement was substituted past imprisonment with penal servitude, and intended to punish. The Penal Servitude Act 1853 (sixteen & 17 Vict. c. 99), long titled "An Act to substitute, in certain Cases, other Punishment in lieu of Transportation,"[52] enacted that with judicial discretion, lesser felonies, those subject to transportation for less than xiv years, could be sentenced to imprisonment with labour for a specific term. To provide confinement facilities, the general alter in sentencing was passed in conjunction with the Convict Prisons Deed 1853 (16 & 17 Vict. c. 121), long titled "An Act for providing Places of Solitude in England or Wales for Female Offenders under Sentence or Order of Transportation."[52] The Penal Servitude Act 1857 (20 & 21 Vict. c. 3) ended the sentence of transportation in virtually all cases, with the terms of judgement initially being of the same duration as transportation.[53] [l] While transport was greatly reduced post-obit passage of the 1857 human activity, the concluding convicts sentenced to transportation arrived in Western Commonwealth of australia in 1868. During the eighty years of its use to Commonwealth of australia, the number of transported convicts totaled about 162,000 men and women.[54] Over time the alternative terms of imprisonment would exist somewhat reduced from their terms of transportation.[55]

Transportation locations [edit]

Transportation to North America [edit]

From the early 1600s until the American Revolution of 1776, the British colonies in North America received transported British criminals. Destinations were the isle colonies of the West Indies and the mainland colonies[ failed verification ] that became the U.s.a..[56]

In the 17th century transportation was carried out at the expense of the convicts or the shipowners. The Transportation Act 1717 allowed courts to sentence convicts to seven years' transportation to America. In 1720, an extension authorized payments past the Crown to merchants contracted to take the convicts to America. The Transportation Human action made returning from transportation a upper-case letter offence.[50] [57] The number of convicts transported to Northward America is not verified: John Dunmore Lang has estimated 50,000, and Thomas Keneally has proposed 120,000. Maryland received a larger felon quota than whatsoever other province.[58] Many prisoners were taken in boxing from Ireland or Scotland and sold into indentured servitude, usually for a number of years.[59] [ page needed ] The American Revolution brought transportation to the North American mainland to an cease. The remaining British colonies (in what is now Canada) were regarded as unsuitable for various reasons, including the possibility that transportation might increase dissatisfaction with British dominion among settlers and/or the possibility of annexation by the United States – besides every bit the ease with which prisoners could escape across the border.

Afterward the termination of transportation to N America, British prisons became overcrowded, and battered ships moored in diverse ports were pressed into service equally floating gaols known as "hulks".[60] Following an 18th-century experiment in transporting convicted prisoners to Cape Declension Castle (modern Ghana) and the Gorée (Senegal) in West Africa,[61] British authorities turned their attention to New South Wales (in what would go Australia).

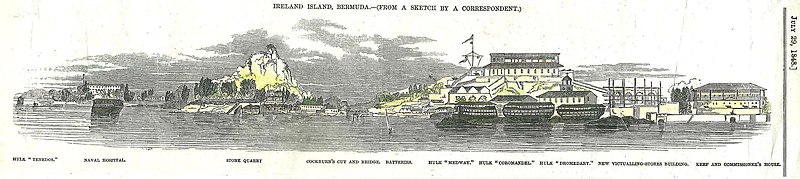

From the 1820s until the 1860s, convicts were sent to the Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda (part of British North America) to work on the construction of the Royal Naval Dockyard and other defence works, including at the East End of the archipelago, where they were accommodated aboard the hulk of HMS Thames at an area still known every bit "Convict Bay", at St. George'due south town.

Transportation to Commonwealth of australia [edit]

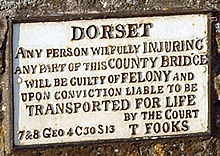

This notice on a bridge in Dorset warns that damage to the bridge can be punished by transportation.

In 1787, the First Fleet, a grouping of captive ships departed from England to found the beginning colonial settlement in Australia, equally a penal colony. The First Fleet included boats containing food and animals from London. The ships and boats of the fleet would explore the coast of Australia by sailing all around it looking for suitable farming land and resources. The fleet arrived at Phytology Bay, Sydney on 18 January 1788, so moved to Sydney Cove (modernistic-24-hour interval Round Quay) and established the first permanent European settlement in Australia. This marked the kickoff of the European colonisation of Australia.[62]

Fierce conflict on the Australian frontier between indigenous Australians and the colonists began only months after the First Fleet landed, lasting over a century. Convicts forced to piece of work in the bush on the frontier were sometimes the victims of indigenous attacks, while convicts and ex-convicts also attacked indigenous people in some instances, such as the Myall Creek Massacre.[63] [64] In the Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars, a group of Irish gaelic convicts joined the Ancient coalition of Eora, Gandangara, Dharug and Tharawal nations in their fight against the colonists.

Norfolk Isle, east of the Australian mainland, was a convict penal settlement from 1788 to 1794, and over again from 1824 to 1847. In 1803, Van Diemen's Land (modern-twenty-four hour period Tasmania) was too settled as a penal colony, followed by the Moreton Bay Settlement (mod Brisbane, Queensland) in 1824. The other Australian colonies were established equally "free settlements", equally non-convict colonies were known. However, the Swan River Colony (Western Australia) accepted transportation from England and Ireland in 1851, to resolve a long-standing labour shortage.

Ii penal settlements were established near modern twenty-four hour period Melbourne in Victoria just both were abandoned shortly afterwards. Later, a costless settlement was established and this settlement later accepted some captive transportation.

Until the massive influx of immigrants during the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s, costless settlers had been outnumbered by penal convicts and their descendants. However, compared to the British American colonies, Australia received a larger number of convicts.[ commendation needed ]

Convicts were by and large treated harshly, forced to work against their will, often doing hard physical labour and dangerous jobs. In some cases they were cuffed and chained in piece of work gangs. The bulk of convicts were men, although a pregnant portion were women. Some were as immature as 10 when convicted and transported to Australia. Most were guilty of relatively minor crimes similar theft of food/clothes/small items, but some were convicted of serious crimes similar rape or murder. Convict status was not inherited by children, and convicts were generally freed after serving their sentence, although many died during transportation and during their sentence.[ commendation needed ]

Convict assignment (sending convicts to work for private individuals) occurred in all penal colonies aside from Western Australia, and can be compared with the practice of captive leasing in the United States.[65]

Transportation from Great Great britain and Ireland concluded at different times in different colonies, with the concluding being in 1868, although it had become uncommon several years before thanks to the loosening of laws in Britain, changing sentiment in Commonwealth of australia, and groups such equally the Anti-Transportation League.[66]

In 2015, an estimated 20% of the Australian population had convict ancestry.[67] In 2013, an estimated 30% of the Australian population (about 7 meg) had Irish ancestry - the highest percentage outside of Ireland - thanks partially to historical captive transportation.[68]

Transportation from British India [edit]

In British India – including the province of Burma (now Myanmar) and the port of Karachi (at present function of Pakistan) – Indian independence activists were penally transported to the Andaman Islands.[69] A penal colony was established there in 1857 with prisoners from the Indian Rebellion of 1857.[lxx] As the Indian independence move swelled, so did the number of prisoners who were penally transported.[ citation needed ]

The Cellular Jail, also chosen Kālā Pānī or Kalapani (Hindi for black waters), was synthetic between 1896 and 1906 as a high-security prison with 698 individual cells for solitary confinement. Surviving prisoners were repatriated in 1937. The penal settlement was shut down in 1945. An estimated 80,000 political prisoners were transported to the Cellular Jail[70] which became known for its harsh atmospheric condition, including forced labor; prisoners who went on hunger strikes were frequently strength-fed.[71]

Utilise by France [edit]

French republic transported convicts to Devil'south Island and New Caledonia in the 19th and early on-to-mid 20th centuries. Devil'due south Island, a French penal colony in Guiana, was used for transportation from 1852 to 1953. New Caledonia became a French penal colony from the 1860s until the stop of the transportations in 1897; about 22,000 criminals and political prisoners (most notably Communards) were sent to New Caledonia.

The most famous transported prisoner is probably French regular army officer Alfred Dreyfus, wrongly convicted of treason in a trial in 1894, held in an temper of antisemitism. He was sent to Devil's Island. The case became a cause célèbre known every bit the Dreyfus Affair, and Dreyfus was fully exonerated in 1906.

Deportations in the Soviet Matrimony [edit]

Unlike normal penal transportation, many Soviet people were transported as criminals in forms of deportation beingness proclaimed equally enemies of people in a form of collective punishment. During the Second Earth State of war, the Soviet Union transported upwardly to 1.9 million people from western republics to Siberia and the Primal Asian republics of the Union. About were persons accused of treasonous collaboration with Nazi Federal republic of germany, or of Anti-Soviet rebellion.[72] Post-obit expiry of Joseph Stalin, near of them rehabilitated. Populations targeted included Volga Germans, Chechens, and Caucasian Turkic populations. The transportations had a twofold objective: to remove potential liabilities from the warfront, and to provide homo capital for the settlement and industrialization of the largely underpopulated eastern regions. The policy continued until Feb 1956, when Nikita Khrushchev in his speech On the Personality Cult and its Consequences condemned the transportation as a violation of Leninist principles. Whilst the policy itself was rescinded, the transported populations did not begin to return to their original metropoles until after the collapse of the Soviet Wedlock, in 1991.[73]

In popular culture [edit]

Performing arts [edit]

Penal transportation is a characteristic of many broadsides, a new type of folk vocal that developed in eighteenth-century England.[74] A number of these transportation ballads accept been collected from traditional singers. Examples include "Van Diemen's Land," "The Black Velvet Band," and "The Fields of Athenry."

Timberlake Wertenbaker's play Our Country's Good is ready in 1780s in the first Australian penal colony. In the 1988 play, convicts and Imperial Marines arrive aboard a First Fleet transport and settle New Due south Wales. Convicts and guards interact as they rehearse a theatre production, which the governor had suggested as an alternate form of entertainment instead of watching public hangings.[75]

In the Tv show American Gods, episode 7 season 1, for i of a side story Emily Browning is playing Essie that is transported twice in her life, bringing with her in America the Leprechaun legend.

In the Idiot box show, Murdoch Mysteries, episode 6 flavour xiv, "The Ministry of Virtue," Murdoch must investigate the expiry of a woman who was sentenced to a bridal version of the penalization. Namely, Murdoch learns of "Virtue Girls," British female person convicts who have accustomed the alternative of agreeing to ally bachelors in Canada instead of beingness sentenced to prison house.

Literature [edit]

One of the key characters in Charles Dickens's novel Cracking Expectations is an escaped convict, Abel Magwitch. Pip helps him in the opening pages of the novel, and he later turns out to be Pip's hush-hush benefactor – the source of his "neat expectations". Magwitch, who had been apprehended shortly after the young Pip had helped him, was thereafter sentenced to transportation for life to New Southward Wales in Australia. While so exiled, he earned the fortune that he later would use to assistance Pip. Further, it was Magwitch's want to see the "gentleman" that Pip had get that motivated him to illegally return to England, which ultimately led to his arrest and decease. Smashing Expectations was published in serial form in 1860–1861.

My Transportation for Life, Indian freedom fighter Veer Savarkar's memoir of his imprisonment, is set in the British Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands. Savarkar was imprisoned there from 1911 to 1921.

Franz Kafka's story "In der Strafkolonie" ("In the Penal Colony"), published in 1919, was ready in an unidentified penal settlement where condemned prisoners were executed by a savage motorcar. The piece of work was later adapted for several other media, including an opera by Philip Glass.

The novel Papillon tells the story of Henri Charrière, a French human convicted of murder in 1931 and exiled to the French Guiana penal colony on Devil'southward Island. A motion-picture show adaptation of the book was made in 1973, starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman.

The British author Due west. Somerset Maugham set several stories in the French Caribbean penal colonies. In 1935 he had stayed at Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni in French Guiana. His 1939 novel Christmas Holiday and two brusque stories in 1940's The Mixture as Before were ready there, although he "ignored the brutal punishments and painted a pleasant picture of the infamous colony."[76]

Penal transportation, typically to other planets, sometimes appears in works of science fiction. A archetype example is The Moon is a Harsh Mistress past Robert Heinlein (1966), in which convicts and political dissidents are transported to lunar colonies in gild to grow food for Earth.[77] In Heinlein's book, a sentence of lunar transportation is necessarily permanent, every bit the long-term physiological effects of the moon's weak surface gravity (about one-6th that of Globe) leave "loonies" unable to return safely to Earth.[78]

Come across likewise [edit]

- Home children

- Millbank Prison

- Penology

- Prison house

- Windrush scandal

- Category:Australian penal colonies

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish; Watkins, Emma (north.d.). "Transportation". Digital Panopticon. Digital Panopticon Project. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Baronial 1650: An Human action for the Advancing and Regulating of the Trade of this Commonwealth". Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660. London: His Majesty's Jotter Role. 1911. Archived from the original on xix September 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2021 – via Institute of Historical Research.

The Parliament of England taking into their care the maintenance and advance of the Traffick Trade, and several Manufactures of this Nation; and being desirous to improve and multiply the aforementioned for the all-time advantage and benefit thereof, to the end that ye poore people of this Land may be set on piece of work, and their Families preserved from Beggary and Ruine, and that the Commonwealth might be enriched thereby, and no occasion left either for Idleness or Poverty:...

- ^ Acts of the Privy Council of England Colonial Series, Vol. I, 1613-1680, p.12. (1908)

- ^ Egerton, Hugh Edward,A curt history of British colonial policy, p.40 (1897)

- ^ "Charles 2, 1670 & 1671: An Act to preclude the malitious burning of Houses, Stackes of Corne and Hay and killing or maiming of Catle". Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved half-dozen March 2017.

- ^ Pickering, Danby (1775). ""An act to authorise, for a express time, the punishment past difficult labour of offenders who, for certain crimes, are or shall get liable to be transported to any of his Majesty'south colonies and plantations."". Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved eight September 2017.

- ^ Transportation Deed 1717, Section 8, p.475

- ^ a b "An act for the effectual transportation of felons, and other offenders, in that office of Smashing Britain called Scotland, and to qualify the removal of prisoners in sure places."

- ^ Donnachie, Ian (1984), "Scottish Criminals and Transportation to Australia 1786–1852", Journal Scottish Economical and Social History, 4: 21–38, doi:10.3366/sesh.1984.4.4.21

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 470

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 472

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 473

- ^ Acts of the Privy Quango (Colonial), vol. I, pp. 310, 314-15

- ^ Cunningham. Growth of Eng. Industry and Com. in Modern. Times; 109, Cambridge, 1892. Cited in Karl Frederick Geiser, Redemptioners and indentured servants in the colony and commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Supplement to the Yale Review, Vol. 10, No. two, August, 1901. "At that place was a popular prejudice against subjecting Christians into slavery or selling them into foreign parts, simply Cromwell did not depict any such distinctions. Not simply did his agents systematically capture Irish youths and girls for consign to the West Indies, simply all the garrison who were non killed in the Drogheda Massacre were shipped every bit slaves to the Barbadoes."

- ^ 30 July 1649 Deed empowering the Lord Mayor, Justices of Gaol commitment for Newgate, to transport threescore prisoners convicted of Felony and other heinous crimes, unto the Summertime Islands or other new English language Plantations.

- ^ Statutes of the Realm: Book 5, 1628-eighty Archived 29 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, p.598

- ^ Statutes at Big, Volume 24, Index for acts passed before 1 Geo. 3 p.581

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 471

- ^ Beattie, 1986, pp. 471–472

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 475

- ^ a b c Beattie, 1986, p. 479

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 480

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 500

- ^ a b Beattie, 1986, p. 502

- ^ a b Beattie, 1986, p. 503

- ^ Beattie, 2001, p. 428

- ^ Beattie, 2001, p. 429

- ^ Beattie, 2001, p. 426

- ^ Beattie, 2001, p. 430

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 504

- ^ Beattie, 2001, p. 432

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 506

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 505

- ^ a b Beattie, 2001, p. 435

- ^ Beattie, 2001, p. 439

- ^ Beattie, 2001, p. 447

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 474

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 483

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 482

- ^ Beattie, 1986, p. 481

- ^ a b Beattie, 2001, p. 444

- ^ Marilyn C. Baseler, "Aviary for Mankind": America, 1607-1800, p.124-127

- ^ Drew D. Gray, Criminal offence, Policing and Penalization in England, 1660-1914 Archived 21 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine p.298 (2016)

- ^ "Penitentiary Act, 1779". Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ ""An act for the effectual transportation of felons and other offenders; and to authorize the removal of prisoners in certain cases; and for other purposes therein mentioned."". 1782. Archived from the original on vii January 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Sentenced beyond the Seas: Australia's early captive records". 15 January 2016. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Australian Discovery and Colonisation". The Empire. Sydney: National Library of Commonwealth of australia. 14 April 1865. p. eight. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ south:Page:History of New Southward Wales from the records, Book 1.djvu/575

- ^ Hugh Edward Egerton, A short history of British colonial policy, p.262–269 (1897)

- ^ a b c d Punishments at the Erstwhile Bailey, Old Bailey Proceedings Online, archived from the original on 12 December 2018, retrieved 20 Apr 2008

- ^ ""An act for enabling his Majesty to qualify his governor or lieutenant governor of such places beyond the seas, to which felons and others offenders may be transported, to remit the sentences of such offenders."". 1790. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b c "Short Titles Act 1896". Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ "Penal Servitude Human activity 1857" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on eleven May 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ Convicts and the British colonies in Australia Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ Transportation and Penal Servitude Archived 7 June 2019 at the Wayback Auto, Mountjoy Prison house Museum

- ^ "Criminal transportation". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved vi February 2019.

Before 1776, all convicts sentenced to transportation were sent to Due north America and the West Indies.

- ^ R v Powell , Sixth session Proceedings of the Old Bailey 10 July 1805 t18050710-23, page 401 (Old Bailey 10 July 1805).

- ^ Butler, James Davie (1896). "British Convicts Shipped to American Colonies". The American Historical Review. 2 (ane): 12–33. doi:x.2307/1833611. JSTOR 1833611. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Ekirch, A. Roger (1990), Spring for America: The Transportation of British Convicts to the Colonies, 1718–1775 , Oxford University, ISBN0-xix-820211-3

- ^ Oxford English Lexicon online, "Hulk" n.2, sense 3b http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/89220?rskey=416nHV&issue=three&isAdvanced=imitation#eid Archived 26 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2017/06/26

- ^ Christopher, Emma (2010). A Merciless Place: The Lost Story of United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland'south Convict Disaster in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Printing (published 2011). p. 5. ISBN9780191623523. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

With the American War of Independence all only lost and promise of restarting the transportation of convicts to the Americas dwindling fast, Britain had begun sneakily banishing its criminals to West Africa.

- ^ Robert Hughes (1988). The Fatal Shore: A History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia 1787–1868. London: Pan Books. p. 82. ISBN978-0-330-29892-vi.

- ^ "Myall Creek massacre". National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019. Retrieved 10 Feb 2019.

- ^ "Myall Creek Massacre and Memorial Site". Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. 25 June 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013.

- ^ "Convict Assignment - National Library of Commonwealth of australia". National Library of Australia. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved viii May 2021.

- ^ McConville, Sean (1981), A History of English Prison Administration: Book I 1750–1877, London: Boston & Henley, pp. 381–5, ISBN0-7100-0694-2

- ^ "Stain or bluecoat of honour? Convict heritage inspires mixed feelings". The Chat. eight June 2015. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved eight May 2021.

- ^ "Department of Foreign Affairs - Emigrant Grants". 28 July 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "History of Andaman Cellular Jail". This is about Andaman Cellular Jail. Archived from the original on eighteen January 2007.

- ^ a b "Hundred years of the Andamans Cellular Jail". The Hindu. 21 December 2005. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ Scott-Clark, Cathy; Levy, Adrian (22 June 2001). "Survivors of our hell". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 7 Feb 2019.

- ^ Statiev, Alexander (2005). "The Nature of Anti-Soviet Armed Resistance, 1942-44: The North Caucasus, the Kalmyk Democratic Democracy, and Crimea". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. Slavica Publishers. 6 (2): 285–318. doi:10.1353/kri.2005.0029. S2CID 161159084.

- ^ Mawdsley, Evan (1998). The Stalin Years: The Soviet Wedlock, 1929-1953. Manchester University Printing. ISBN9780719046001. LCCN 2003046365.

- ^ Rouse, Andrew C. (Jump–Fall 2007). "The Transportation Ballad: A Song Type Rooted in Eighteenth-Century England". Hungarian Periodical of English and American Studies (HJEAS). Middle for Arts, Humanities and Sciences (CAHS), acting on behalf of the University of Debrecen CAHS. thirteen (1/2, The Long Eighteenth Century): 93–103. JSTOR 41274385.

- ^ Rokotnitz, Naomi (2011). Trusting Performance: A Cerebral Arroyo to Apotheosis in Drama. New York, New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 87. ISBN978-1-349-59433-7. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (2005). Somerset Maugham: A Life. Vintage Books. p. 218. ISBN1-4000-3052-8. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ Chocolate-brown, Alan (31 January 2019). "Is The Moon is a Harsh Mistress Heinlein's All-Time Greatest Work?". Tor.com. Macmillan. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A. (1966). The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

Just most Loonies never tried to get out The Stone--too risky for whatever gars who'd been in Luna more weeks. Computermen sent up to install Mike were on short-term bonus contracts--get task washed fast before irreversible physiological alter marooned them 4 hundred thousand kilometers from home.

References [edit]

- Pardons & Punishments: Judges Reports on Criminals, 1783 to 1830: HO (Home Office) 47 Volumes 304 and 305, List and Index Society, The [British] National Archives

- Beattie, J.M. (1986), Offense and the Courts in England 1660–1800, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN0-19-820058-7 .

- Beattie, J.Chiliad. (2001), Policing and Penalisation in London 1660–1750, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN0-xix-820867-vii .

- Ekirch, A. Roger (1987), Spring for America. The transportation of British convicts to the colonies, 1718–1775 , Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN0-19-820092-7 .

- Hitchcock, Tim; Shoemaker, Robert (2006), Tales From the Hanging Court, London: Bloomsbury, ISBN978-0-340-91375-8 .

- Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish. "Convict Transportation from Great britain and Republic of ireland 1615–1870", History Compass 8#eleven (2010): 1221–42.

- Punishments at the Sometime Bailey, Former Bailey Proceedings Online, retrieved 11 November 2015

- Robson, Fifty. Fifty. (1965), The Convict Settlers of Commonwealth of australia, Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, ISBN0-522-83994-0 .

- Sharpe, J. A. (1999), Crime in early modern England 1550–1750, Harlow, Essex: Longman, ISBN978-0-582-23889-3 .

- Shoemaker, Robert B. (1999), Prosecution and Punishment. Piffling crime and the police force in London and rural Middlesex, c. 1660–1725, Harlow, Essex: Longman, ISBN978-0-582-23889-iii .

External links [edit]

- U.k. National archives

- Convict life – State Library of NSW

- Convict Transportation Registers

- Convict Queenslanders

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penal_transportation

0 Response to "what event ended the transportation of felons to north america"

Post a Comment